The tech industry needs to change its work culture to recruit more women

Changing the expectation that staff should work around the clock could encourage more women to work in technology, according to Gilda Seddighi.

Gendered educational and career choices are often referred to as the Nordic dilemma, and are subject to discussion both in politics and research.

One of the worst offenders is the technology sector, which is very male-dominated. Statistics for this sector show that women are consistently very poorly represented in education, employment and in research.

Professor and researcher Gabriele Griffin from Uppsala University recently published a book that brings together recent research on the gender imbalance in technology-driven innovation and research.

The editor points out in the introduction that the situation differs in the Nordic countries, which operate with different political and regulatory equality measures. What they do have in common, however, is a number of gendered disciplines.

Roundabout path to a career

One of the contributors to Griffin's book is senior researcher Gilda Seddighi. She wrote the article, If It Had Been Only Me, It Would Not Have Worked Out: Women Negotiating Conflicting Challenges of ICT Work and Family in Norway, together with professor and researcher Hilde G. Corneliussen.

Gilda Seddighi explains that the article is based on data obtained through interviews with 22 women during the period 2017–2018, and that the data form part of a large research project.

“Can you tell me more about these women?”

“The women live in Western Norway and range in age from 37 to 59. Their jobs include regional innovation, development positions as well as positions in research and funding agencies. One of the selection criteria was that the participants had at least one bachelor's degree.”

“We subsequently concluded the following: One candidate had a bachelor's degree, seven had a doctorate, and the rest had taken master's degrees. Nine of them had taken education specifically related to technology,” says Seddighi.

The senior researcher goes on to say that the women lived with their partners and had responsibility for between one and four children. Some of the women also had children from multiple relationships.

“The fact that they were caring for children in a family setting was key to what we wanted to look at: Namely, the challenge of working in a demanding position and managing a family,” she says.

“What was the most surprising finding you made?”

“One important finding that became clear in the Nordwit project, which our project is part of, was that about half of the women were not recruited to tech positions via the usual ‘educational route’. These women ended up in their positions via three paths."

“One was building tech skills later in life, after they had completed their education and started working. Another explanation was that their work duties had evolved to require more tech expertise, and the last path was an emergent need for non-technologists in tech positions.”

The fact that education and tech jobs do not follow the usual course, where you first find out what you want to be, then take an education and find a job that suits, is important knowledge, the researcher believes.

“Can you explain why this is relevant?”

“In Norway, only 25 per cent of tech students are women. This low figure distorts the OECD stats, because they use education statistics as a basis when measuring whether or not professions have a good gender balance.”

“Did you find any pattern that can explain why the women did not choose to study technology subjects in the first place?”

“There were several explanations for this. Several of the women said they didn't know it was an option, some pointed out that they didn't believe they were good enough at maths, while others saw it as a 'boy's subject'," says Seddighi.

Flexibility to a fault

An interesting finding in Seddighi and Corneliussen’s material is that it was not the fact that they were required to work full-time that the women found problematic and demanding. Rather, it was the culture of flexibility – and the requirement to work more than full-time.

To find out what was important to their career path, the researchers chose to divide the women into two groups: Women who only worked full-time and women who worked more than full-time.

“Those who only worked full-time said that they could not or would not advance their careers because it would compromise family time. They said that they neither wanted nor were able to meet the workplace demand for flexibility.”

Examples of such flexibility include attending late meetings, having to go on work trips or taking extra courses,” according to Seddighi.

“What about the other group, those who worked more than full-time?"

“Those who felt they worked more than full-time indicated that having a partner at home enabled them to prioritise their job. Their careers depended on a partner with an occupation or profession that was less demanding and therefore allowed them to take more responsibility at home,” she says.

The senior researcher explains that flexibility in working life is often referred to as positive for workers, because it provides room for adaption and adjustment. Flexibility within a tech career, however, means always being available for work, which in turn makes working hours unpredictable.

“Does that mean the culture of flexibility is a bottleneck in the careers of women in tech professions?"

“Yes, because flexibility in practice means you have to work longer hours than other people, which is incompatible, at times, with family life and children in need of care and attention."

“The solution needed to bring about change and get more women to pursue a tech career is thus to change the work and flexibility culture."

"For many, the work pattern and boundless work culture – which seems to be the pattern – are too invasive, and impact both family life and the work-life balance,” says Seddighi.

Translated by Allegro Language Services.

The book Gender Inequalities in Tech-driven Research and Innovation: Living the Contradiction contains a collection of articles by researchers who write about the position and role of women in technological research and innovation.

The subtitle "Living the contradiction" refers to the contradiction that some professions and education programmes in the Nordic countries are very gendered, despite an otherwise high level of equality.

The book is edited by Gabriele Griffin, professor at the Centre for Gender Research at Uppsala University. Gilda Seddighi and Hilde G. Corneliussen have written the article If It Had Been Only Me, It Would Not Have Worked Out: Women Negotiating Conflicting Challenges of ICT Work and Family in Norway.

More about Nordwit:

Hilde G. Corneliussen is project manager, and Gilda Seddighi and Carol Azungi Dralega work on the Nordwit project at the Western Norway Research Institute. Nordwit is short for Nordic Centre of Excellence on Women in Technology Driven Careers.

The project, which started in 2017, is funded by NordForsk and is a collaboration between Uppsala University, Tampere University and the Western Norway Research Institute.

The theme of the project is women's careers in technological research and innovation in academia and beyond. The goal is a better gender balance in technology-driven research and innovation.

Read more at Western Norway Research Institute

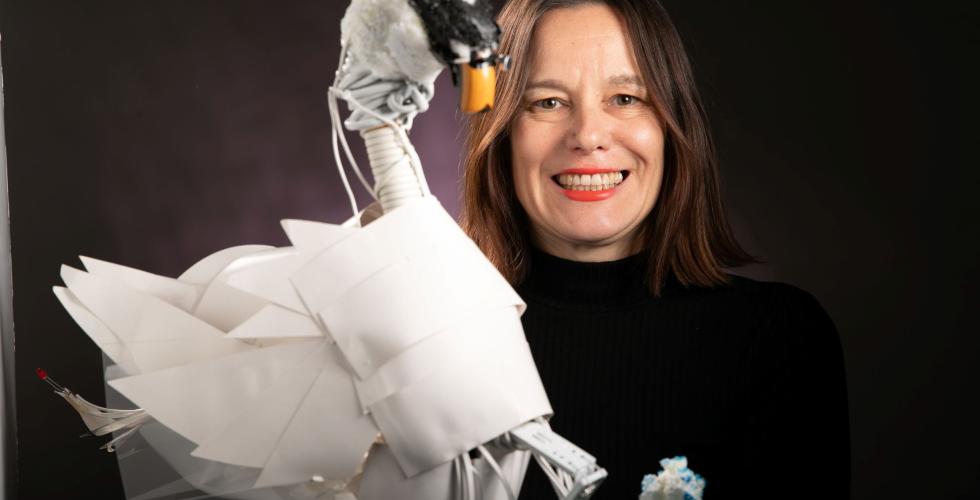

Gilda Seddighi:

Gilda Seddighi is a senior researcher at the Western Norway Research Institute and wrote her doctoral thesis "Politicization of grievable lives in Iranian Facebook pages" (2017) at the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Bergen (UiB). She has been affiliated with both the Department of Information Science and Media Science, and the Centre for Women's and Gender Research at UiB.

Source: Western Norway Research Institute

Statistics

In 2021, less than one-third of those who received a doctorate in technology were women:

- 29 per cent were women, 71 per cent were men.