Technology professor wins two gender equality awards

“I felt that now I need to give something back,” says Letizia Jaccheri. She was named this year’s ODA Awards Woman and recently won a gender equality award at NTNU.

Jaccheri is a professor at NTNU’s Department of Computer Science. Fresh off winning the ODA Award, she also won an NTNU award for her work in championing gender equality and diversity.

Both jury statements highlighted her involvement in recruiting women to pursue a technology education as well as her research under two projects at NTNU: Girl Project Ada, and the IDUN recruitment project under the Research Council of Norway’s BALANSE programme.

“IDUN was my brainchild,” says Jaccheri.

“I have always thought the Ada project is terrific, but 10 years ago it began gnawing at me that we weren’t doing anything to recruit women from the PhD level and above.”

No recruitment measures beyond master’s level

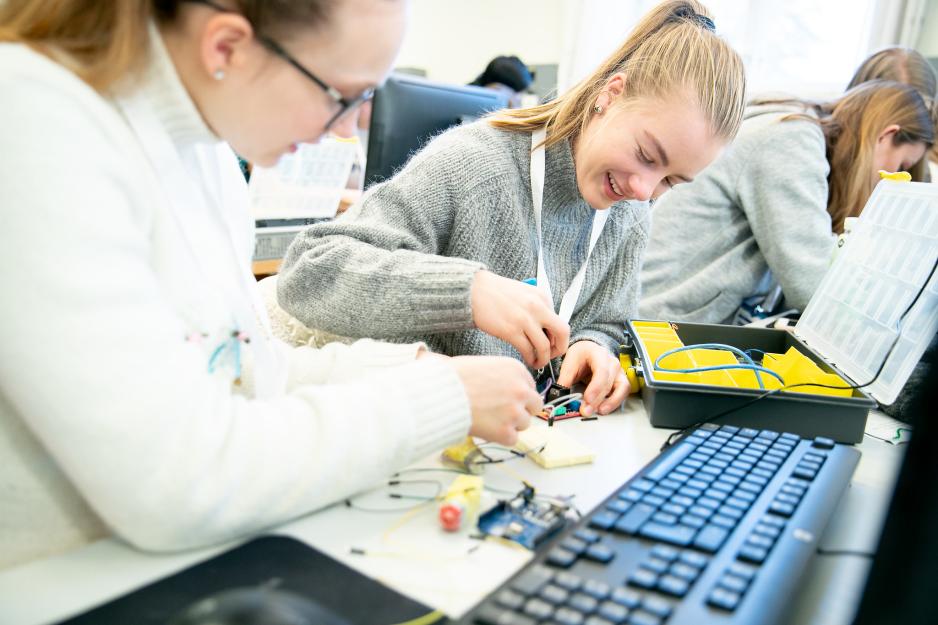

Girl Project Ada has a long history at NTNU. Ada’s objective is to ensure that more women complete their studies in NTNU’s male-dominated technology programmes – and then get jobs in technology fields. This begins by creating a good study environment for girls through a range of activities, and working closely with the private sector to provide the girls with a useful network in the technology community before they finish their studies.

“Ada is about making sure the girls are enjoying their studies and finding jobs in industry, and that is wonderful. But I saw that in our own Faculty of Information Technology and Electrical Engineering, we had few women in recruitment positions [doctoral and post-doctoral fellowships] and none in leadership positions.”

“No Norwegian girls were taking a PhD. We had to do something about that,” explains Jaccheri.

“In 2013 I became head of my department. So initially I thought, ‘Now we’ve succeeded, we have the first female department head’. But then I realized I was the only woman in leadership and I thought, what do I do now?”

“So I began applying for funding from the university and from the Research Council.”

Nine women all at once

This culminated in the BALANSE programme’s “IDUN – from PhD to professor” project.

The project is named after Idun Reiten, one of Norway’s most eminent mathematicians and the faculty’s first female professor. Preparations were years in the making, but in 2019 the IDUN project could finally embark on its ambitious goals.

“We hired nine women for Professor II positions, which means they each had 20 per cent of a full-time position at NTNU. This gave the young doctoral students and researchers more role models than the few women professors here from before,” says Jaccheri.

Prior to IDUN, just 14 per cent of the faculty were women. From autumn 2020, the nine Professor II women were hired for two years, and they are serving as mentors and role models in the faculty.

“They mentor 35 people, both men and women organized into thematic research groups under the nine professors. The pandemic has prevented all but two of the nine to physically come to NTNU. But they have all participated actively, with many meetings, and they help the young researchers.”

Due to the pandemic, however, the project’s future is not fully determined. The original intent was for the nine women, after their first year, to take responsibility for building relations with their departments with the aim of renewing their employment contracts and becoming full NTNU professors.

“But the pandemic perhaps hasn’t allowed them to fully prepare for that. So now we are taking some time to consider how to proceed with IDUN, and what the nine hope to do in the future,” explains Jaccheri.

A Europe-wide challenge

She hopes to be able to delegate more of the administrative duties of running IDUN to others, in order to focus more on her own discipline, computer science.

She has also taken on the leadership role in the EU project EUGAIN (European Network for Gender Balance in Informatics), launched in autumn 2020. The underrepresentation of women in ICT (information and communications technology) is certainly not limited to Norway – it is the case throughout all of Europe, and progress has been slow.

“Through EUGAIN we will address five main challenges,” says Jaccheri.

“The first is the transition from school to higher education: how to encourage girls to choose to study ICT. The second is transitioning from master’s studies to becoming a doctoral student. The third challenge is the leap from PhD to professor, which is the level that IDUN operates on. The fourth is about cooperating with industry and society, while the fifth involves communicating results from the project to both society and other researchers.”

Working on a European level helps Jaccheri put Norwegian efforts in perspective, she feels. It is not a case of Norway being far behind, in fact quite the opposite. All of Europe is facing the same challenges.

Doctoral degree is a bottleneck

“The transition from upper secondary school to university is the most popular level to work on, and where people have the most opinions. This is also true in Norway, where we’ve been running the Ada project for 20 years,” says Jaccheri.

“But few people give much thought to the advance up to doctoral-level studies. Through the Ada project, we recruit girls from all around Norway and we instruct them in network- and career-building. But then, when a doctoral fellow position opens up, we primarily recruit candidates from abroad. This is why it’s important to implement the same kinds of measures at the doctoral level, so the foreign research fellows who come here receive similar instruction in network- and career-building to what the Norwegians get at the master’s level.”

She believes that addressing the fourth challenge, regarding cooperation between the private sector and the research and higher education system, has much in common with ODA’s efforts in Norway. ODA is a network for women in technology fields that works to enhance diversity in the sector and promote technology as an attractive career choice for women.

Jaccheri admits that until recently she knew little about what this network does.

“In Trondheim we are used to having closer relations with the rest of the world than with Oslo, perhaps in particular those of us who are foreigners. I myself have been both a mentor and a mentee in ODA, but there were only two of us in Trondheim mentoring each other and sharing coffee on Fridays, so we lived somewhat in our own world.”

“Norway is inspiring”

Now she is concerned with tuning in more to what is happening in the rest of Norway in terms of gender equality in technology fields.

“Often there is more inspiration to gain from Norway than internationally, which has been a great revelation for me. The researchers associated with the BALANSE programme, for instance, know a lot about gender and technology, but they may not be very visible internationally. So linking the work being done in Norway to the European level and beyond, that is what I want to find out more about.”

Jaccheri has been employed at NTNU for over 20 years. Originally from Italy, she first came to Norway as an exchange student in 1989. She traces her commitment to gender equality issues back to that stay. Gender equality was not something she had reflected upon much in her study days in Italy, perhaps since there were actually quite a few women who studied computer science with her, some of whom went on to become professors in Europe.

“My interest in gender equality began mainly via my supervisor at NTNU, Professor Reidar Conradi. Later, when I was a young associate professor, a professorship position opened up, earmarked for a woman. He arranged it so the position would be in computer science so that I could apply.”

“When I got that position, I felt that now I need to give something back to show I was a good investment.”

Looking to create change in the discipline

What primarily drives Jaccheri to work with gender and diversity in the field of ICT is that it is everywhere and in so much of what we all do.

“IT systems are used by women and men, healthy and sick, ethnic Norwegians and everyone else. So Norwegian men over 50 should not be the only ones deciding how these systems are designed. Remember back to when airbags were introduced – it turned out they were tested on men who weighed 80 kilos, and airbags killed some women and children because of it.”

“There are lots of examples like this. Diversity among those developing technology is absolutely essential,” believes Jaccheri.

This is why, she reminds us, the goal must not be simply to increase the numbers of women at all levels of the research and higher education system. We must also consider how to enhance the actual discipline.

Jaccheri’s research at NTNU examines, among other topics, gender issues when artificial intelligence is introduced.

The importance of gender equality for sustainability

“Our starting point is UN Sustainable Development Goal 5, about gender equality and empowering women and girls. We try to link elements of this goal with components of artificial intelligence to explore what may impede, or promote, gender equality.”

Jaccheri cites cases where the use of artificial intelligence in job recruiting can lead to negative impacts on gender equality – because the AI systems were trained on male-dominated data sets, thus eliminating women from the applicant pool virtually automatically. She is learning more about factors of this kind.

Increasingly, she is convinced that gender and diversity aspects need to be incorporated into research and teaching, not merely dealt with at an administrative level.

“And in the context of development, I believe that gender equality is a crucial Sustainable Development Goal in itself, while also having an impact on many of the other SDGs. In Norway we are good about promoting sustainability, and now we need to consider gender equality in context with the other SDGs,” concludes Jaccheri.

Translated by Darren McKellep.

Letizia Jaccheri is an NTNU professor at the Department of Computer Science, Faculty of Information Technology and Electrical Engineering.

Her areas of expertise include computer science, interaction design and computerized gaming.

Jaccheri recently received two gender equality awards: this year’s ODA Awards Woman and the NTNU Gender Equality and Diversity Award. She is involved in the Ada project and the IDUN recruitment project under the Research Council’s BALANSE programme.

More about IDUN - from PhD to professor

More about Girl Project Ada

More about the ODA network and the ODA Awards 2021

Read about the Gender Equality and Diversity Award at NTNU

Contact information: Letizia Jaccheri