"Physics can be feminine"

The world will be a better place if more girls become engineers, says Camilla Schreiner. She does research on the connection between gender and choosing a career within the Natural Sciences.

"Girls know that they can choose the same career path as guys, but they don’t want to. The challenge lies in how to show them that science studies can be 'girlie', and that scientists make the world better."

These are the words of meteorologist and scientist Camilla Schreiner at the Norwegian Centre for Science Education at the University of Oslo. She believes that youth culture, gender identity and role models are key elements when planning a career. Her new research project, Vilje-con-valg, deals with how youth choose or not choose science studies. Their priorities and choices will be studied through quantitative and qualitative research with the aim of identifying the criteria and priorities which cause girls and boys to choose or not choose science studies.

Reluctant to study gender

Schreiner’s doctoral thesis, Exploring a ROSE-garden: Norwegian youth's orientations towards science ? seen as signs of late modern identities, was based on the international research project ROSE ? The Relevance of Science Education. This project dealt with the attitudes 15-year-olds have towards science studies. At the time, Schreiner was reluctant to employ a gender perspective.

"I wasn’t interested in that. Quite the contrary. I didn’t want to have gender differences as a starting point. I felt that there were other, more interesting ways to categorise youth. But gender turned out to be important," she says.

Schreiner’s creative approach was to categorise the youths based on their answers. She ended up with eight different groups of pupils, each with their own characteristic profile, with certain interests and attitudes regarding science studies.

"But when I looked at the composition of the groups I noticed that they were gender specific. The groups were virtually all-female or all-male. I was surprised, but gender is a decisive factor. So with Vilje-con-valg we have chosen to make the gender perspective a central element."

Why do they choose so differently?

In the autumn of 2008, Schreiner and her research colleague Ellen Karoline Henriksen will collect data from students at all institutions that offer science studies. The project has a dual purpose. One is to tackle a problem in society. The project will offer critique and advice with regards to teaching methods.

"We also want to develop a better theoretical understanding of why girls and boys choose so differently. Hopefully, some of our PhD students will examine this matter," says Schreiner.

"There are vast differences between girls and boys, and there are also differences between girls and girls. But there is a strong link between gender and those values, ideals, and attitudes youth express with regards to choosing a career," she states.

Modern – not traditional

Camilla Schreiner has her own theory:

"It is a well-known fact that Norway is one of the world’s most progressive countries when it comes to equal opportunities for girls and boys. At the same time, our work force is extremely gender segregated. This division line is considered 'traditional'. In my opinion it is modern. This is how Norwegian youth like to see themselves. Girls feel that they can choose between something that suits them and something that doesn’t suit them. So they choose something they feel suits them."

According to Schreiner, this is related to our culture and the modern zeitgeist. And it is related to how science studies are portrayed.

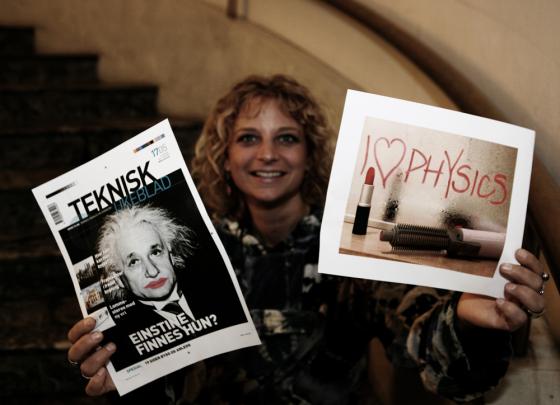

"We can’t encourage girls to choose like boys. They won’t do that. Instead, we have to show them that science studies can be feminine – that they can suit girls and their values and ideals." She picks up a copy of the science magazine Teknisk Ukeblad. Einstein is on the cover – complete with eye shadow and lipstick.

"A humorous attempt to show that physics can be feminine. Pushed to its extreme, this is the way to go. We have to show girls that physics can suit them, and then hope that they choose it."

"Girls often express a desire to make the world better. Therefore they want to become doctors, psychologists or veterinarians, or they study the Humanities. In order to get more girls interested in engineering we have to show them that these professions make a positive contribution," Schreiner states.

Afraid to be geeks

Schreiner believes that a sustainable society requires new and different technological solutions to meet our modern needs. "Engineers play a central role in this work. We need to find a new way to convey this fact to girls."

It is more acceptable for guys to be geeks, she says.

"Guys, more than girls, can be interested in a certain phenomenon without considering if it is relevant to society or how it can be put to use. It is more legitimate for guys than girls to study things like physics just because they find it interesting."

Idealism is necessary

Girls want to be able to say that their career choice is important and meaningful, says Schreiner. She believes that technology is just that.

"Think of certain elements of technological development. We have wafer thin computers and mobile phones with thousands of possibilities. At the same time we lack technology to make use of alternative energy sources. Does that say something about who is behind the technology? If more idealistic girls were involved in developing technology we might have had slightly bigger computers, but more environmental-friendly solutions. We have to show girls that this is a way to make the world better."

This article is also publicised on www.kilden.forskningsradet.no.

Translated by Vigdis Isachsen

Vilje-con-valg’s main goals are to:

- Gain new knowledge on how young adolescents make their career choices and how science studies fit into the picture.

- Develop new theoretical perspectives.

- Promote an informed debate and contribute with critique, comments and advice with regards to teaching methods in schools and universities, general information, and target groups for recruitment projects.

Data will be collected in August and September 2008 with the use of questionnaires. Schreiner and Henriksen will conduct telephone interviews with students who drop out of science studies.