Time use in academia: Men and women use their time differently, but everyone works too much

Male post-docs and PhD candidates work more than their female colleagues, but female professors work the most hours of all, according to the latest time use survey.

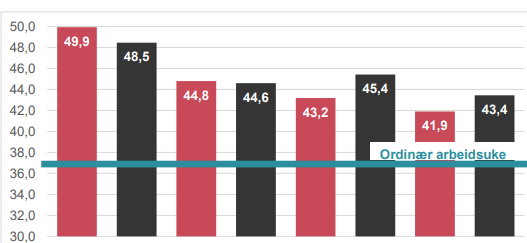

Academic and professional employees at universities and university colleges work 44.7 hours per week on average. This is considerably more than the 37.5 hours that is typical for state employees. Topping the list are female professors with 49.9 hours per week. Except for teaching, female professors do a little more of all other types of tasks than their male colleagues.

This is shown in a survey conducted by the Nordic Institute for Studies in Innovation, Research and Education (NIFU) in which all academic and professional employees at Norwegian universities and university colleges were invited to provide information about how they divide their work hours among various tasks.

The purpose of the survey was to compile an overview of the amount of time spent on research and development (R&D) at higher education institutions.

Less time on research

Although the survey did not initially focus on gender differences, senior adviser Hebe Gunnes noticed a number of differences between women and men in various academic positions.

“We have some interesting data that can be analysed further, and the most interesting is that women spend less time on research and development than men,” she says.

“When academics are in a phase of life when they work less, it’s their R&D time that suffers the most. This may be because it’s easiest to juggle their research hours, while it’s more difficult for them to control how much time they use on other tasks as they would like. After all, teaching and administrative tasks must be done, and time spent on research dissemination, for example, can depend on when conferences are held and what papers get accepted,” says Gunnes.

Of the 8,570 academics who gave an estimate of how they divide their work hours, the PhD candidates and post-docs stated that they used the most time on R&D, with 76 and 72 percent respectively.

Female post-docs and PhD candidates work less

While female professors stated that they work 1.4 hours more on average than their male colleagues, the results among post-docs and PhD candidates were the opposite. Male post-docs reported that they work 2.2 hours more per week on average than their female counterparts, and male PhD candidates worked 1.5 hours more than the women. The difference comprises the time spent on R&D.

Both male and female respondents stated that they use about the same amount of time on other tasks, with the exception of administration, which the female post-docs said they spend a little more time on than their male colleagues. This is the opposite for the PhD candidates.

Breadwinner responsibility can cut into R&D time

According to Hebe Gunnes, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the reasons for these differences just by looking at the statistics, but the information from the survey’s comment field can give an indication.

“We did not ask the respondents if they have children, but this is one of the reasons given in the comment field. If you have children and have the main responsibility for the home, you are simply not able to work as much as you would have otherwise. It’s more difficult to raise children when you are a PhD candidate or post-doc than when you are a professor, and it’s certainly more difficult to find time to work when the children are young,” says Gunnes.

One of the comments in the survey is from a respondent who is frustrated about the limited time she has for research due to her family situation:

“I’m a sole provider (...) and so I’m confined to ‘normal work hours’. My research suffers most in terms of earlier and considerably longer work hours,” she writes.

A number of comments come from employees who state that they use a lot of their leisure time on work tasks or on research outside of work hours:

“In the best case, I do my research in my spare time, but most of the time when I’m not supervising or teaching, I’m applying for research funding. It’s a senseless use of time,” writes another respondent.

“I don’t count hours. Being an academic is a lifestyle,” writes another.

Can differences between subjects and institutions explain gender differences?

State Secretary Rebekka Borsch of the Ministry of Education and Research also thinks it is difficult to make a firm statement about the reasons for the differences revealed in the NIFU survey.

“This is speculation, but it could be that women are more amenable to taking on administrative work. The survey results may also reflect idiosyncrasies of the research method, for example, if the women who responded estimate their number of work hours differently from the men. It’s not unlikely either that differences between the subjects or institutions affect the results, since there are many more female professors at certain institutions and in particular subjects,” she explains.

“What can be done to create conditions so that women and men have equal opportunities in the sector?”

“Of course women and men should have equal opportunities, and the sector cannot treat people differently based on their gender. The sector must ensure that it is an appealing place to work for both genders and establish reliable career paths with permanent positions. In this regard, the Ministry of Education and Research expects the KIF Committee to contribute its knowledge of the challenges and measures within the sector,” says Borsch, and adds that the Research Council of Norway also pays close attention to gender balance.

Borsch is unsure how much having breadwinner responsibility causes female post-docs and PhD candidates to work less than their male colleagues.

“I see that NIFU mentions this as a possible explanation in its survey. The ministry expects institutions to create conditions so that both genders have equally good opportunities for success,” she says.

According to Borsch, the various institutions also have a responsibility to assess whether laws and agreements are being broken when professional and academic staff in the sector report that they work more than the norm for state positions and that many must use their leisure time to find time for their research.

“On the other hand, we see progress in this area, since the employees in the sector responded that they worked 44.7 hours per week in 2016 as compared to 48.5 hours in 2000.”

Small changes from previous time use surveys

The last time use survey of staff at universities by NIFU concerned the year 2000. NIFU also conducted a survey of university college employees for 2005. In 2011, the Work Research Institute (AFI) carried out a time use survey for both universities and university colleges for 2010, and in this connection NIFU conducted a supplementary survey.

NIFU found only small changes in the distribution of time use in the period from 2000 to 2016. One of the changes is more time spent on academic supervision of master’s degree students and PhD candidates, a group which increased substantially during that period. At the same time, the survey shows a decrease in time spent on research dissemination and other so-called “external” tasks.

With regard to gender differences, AFI’s survey shows that men without children worked the most hours in 2010, while women with children worked the fewest.

In general, women work fewer hours than men, regardless of whether or not they have children, although women’s work hours seem to be affected more by children,” stated the AFI’s report published in 2012.

The difference between male and female professors and associate professors was rather small; among the respondents in AFI’s survey, the women stated that they worked 49.3 hours on average, while men worked 49.1 hours.

Statistics from the latest time use survey showing the difference between male and female post-docs, in which the men stated that they work 2.2 hours more per week than the women, correspond with the findings from AFI’s survey. In 2010, male post-docs worked an average of 47.7 hours per week, while their female colleagues worked 45.7 hours. In 2016, the work hours of both genders decreased slightly more than two hours.

Translated by Connie Stultz.

The time use survey was conducted by the Nordic Institute for Studies in Innovation, Research and Education (NIFU) in 2017.

Read the results in NIFU's working paper (in Norwegian only).

In 2011, the Work Research Institute (AFI) carried out a time use survey for both universities and university colleges for 2010.

Read the time use survey at AFI (in Norwegian only).